I first heard Bryn Harrison’s surface forms (repeating) at its premiere at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in 2009. Here is part of what I wrote then (and here is the rest):

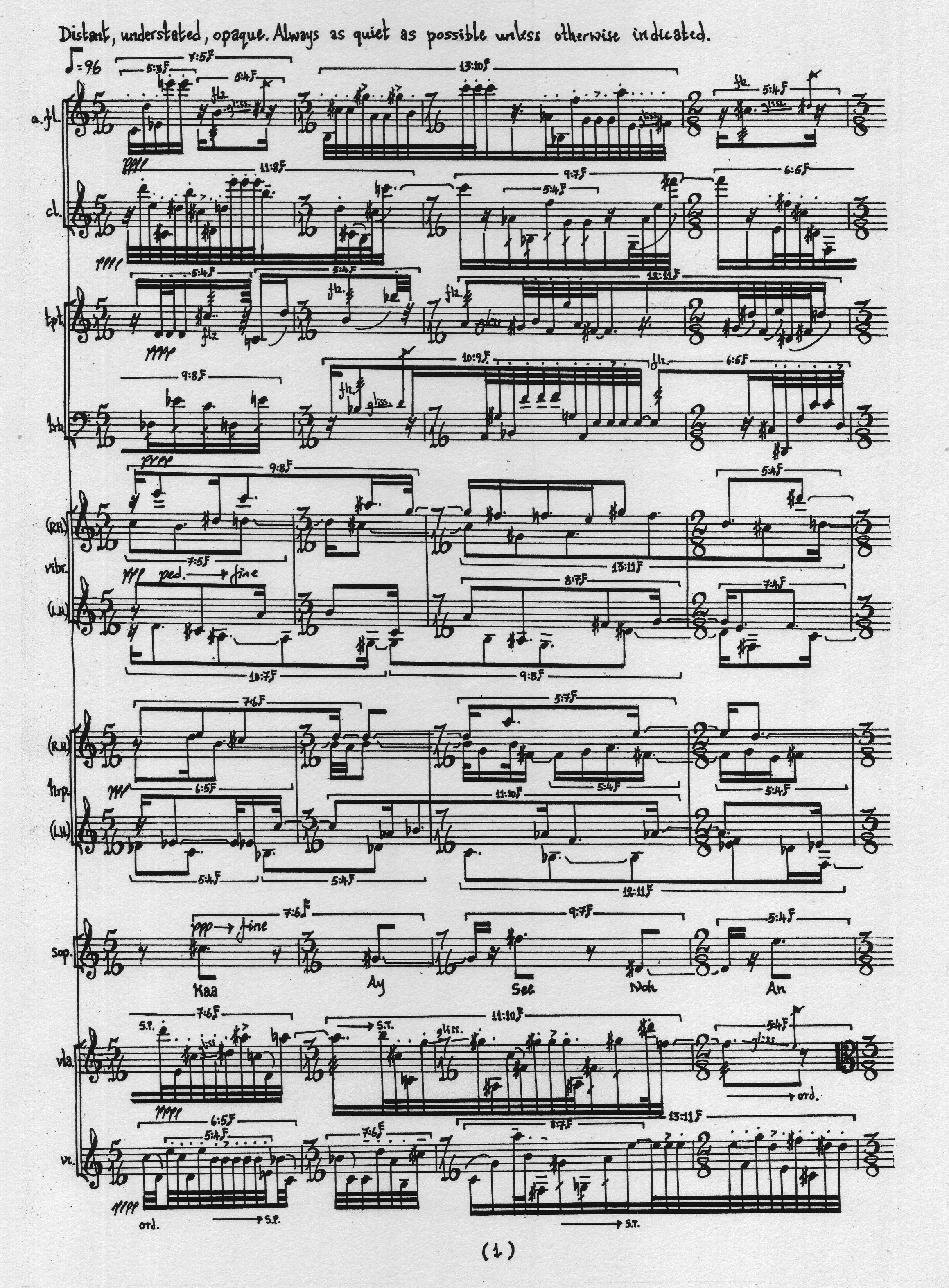

surface forms (repeating) was a wonderful meeting point (not a compromise) between Harrison and ELISION. The players were in perpetual, rapid motion for the full ten and a half minutes. The dynamic level always stayed low. There was a tremendous tension sustained throughout. And for me, part of the complete focus that it commanded was the continual asking of the question, what is it? The sound world seemed to me to be either microscopic or cosmic in its dimensions. Finally I landed on the image of a tiny nucleus controlling the action of an entire planet of water. The form of the whole is constant and unchanging, but everything within that form is constantly changing. There is a very useful interview with Harrison in the new book edited by James Saunders: The Ashgate Research Companion to Experimental Music. Without quoting too extensively, these couple of sentences about his working process shed some light on the piece I heard on Thursday: “I began to see each bar almost as an area of compression, in which I could subtly contract, expand or in some way distort the rhythms. I would then overlay, combine or link material into longer chains of note values to form whole sections of music or even entire pieces.” It was awe-inspiring to watch any one of the players, but there was no way to get away from the fact for more than a moment that they were operating as a collective unit.

Now that I have the recording, it’s a real opportunity to make some clearer decisions about how to engage with the piece. My own richest experience of the recording is with the close immersion of good headphones. That way, I get the most possible glimpses, fragmentary as they are, of the thousands of details that are slipping past me. I am more, rather than less, bewildered by the piece with each listening, and still cannot reconcile myself to Harrison’s statement below (though I believe him) that the material loops every 40 seconds. The arc and scope of the piece feels much broader than that. There is a flattening of hierarchy between instruments, and the audible surface of the sound is constantly flickering between them.

I had a second chance to engage with a live performance of the piece in March 2010 in London, and to speak with Bryn about it afterwards.

One thing I noticed, looking back at the program note from Huddersfield for surface forms (repeating) was a sort of a set of paradoxes in what you were writing. You talk about “at once both static and mobile,” “providing points of orientation/disorientation,” “drawing a listener into the surface,” where I would usually think of being drawn into the interior, but not into the surface. And then in general there is a circular ways of dealing with time in what is more or less a linear medium. I’m wondering if paradoxes seem pretty essential to you as a composer.

I don’t intentionally set out to make paradoxes, and in fact I don’t think I was aware of the paradoxical nature of that writing either. But I am interested in a sort of putting forth an undefinable quality within the music, something which on the one hand is understandable, has a certain coherence, perhaps even has a certain logic, and yet attempts to transcend that logic as well. So you’re left with both a sense of some kind of understanding, some kind of coherence to the music, but simultaneously a sense of perhaps not really knowing what it is that you’ve heard. So perhaps the paradox comes through. Can it be a paradox without a contradiction?

I think so, and I hear that in your work.

I think a lot of the visual arts that I’m interested in do that as well. If I look at the paintings of say Bridget Riley, the more you look at them, the more there’s a sense of construction of how the thing’s made, and yet at the same time it kind of eludes itself. It transcends the process, if you like. So Bridget Riley in particular talks about how she wants to make colored forms but she doesn’t want to color forms. It’s the result of how things are put together that throws up a sensation of something that hasn’t been painted. I suppose it’s that same kind of thing in musical terms, that you know you can use certain processes. In the case of my music, I sometimes combine, say, a rhythmic process with a melodic process. But the result of that is something which I can’t predict. So as a listener, it still feels fresh to me.

Another thing that strikes me about your music and some others around, is that it’s music that pretends to be less than it is.

Pretends to be less than it is? [laughs]

Yeah. You hear it, and the pitch material adds this layer of, oh, it’s just that. But then underneath, there are all kinds of things happening. I wouldn’t say it’s deceptive in that way, but it’s another kind of contradiction that I hear.

Yeah. There’s that sort of dictum in minimal art where simplicity of form isn’t necessarily simplicity of experience. You can have something that on the surface appears very straightforward, and yet the experience of seeing that work or in this case of listening to music is a lot more complex than it pretends to be, as you put it.

And I’d say too that the construction of it isn’t simple either. There’s a lot of thought that goes into that, and it’s smoothed over in some surface way, but not actually.

Yes, yeah.

I was surprised when I heard surface forms (repeating) the first time. Knowing something of your work from before, and knowing the work that ELISION does in general, to me they seemed like fairly divergent aesthetics. But to me it sounded like you found a true meeting point, like it was really a piece for ELISION and your piece, a part of your work. I’m wondering how you got there.

It was quite a long process, actually. Very often, when I’m working on a piece, it goes through a lot of not just revisions but actually restarts. So from where I start with an idea to where I end is often quite a long process.

Does the beginning have any relation to the end result?

I think so. And I think the pieces always contain the trace of where they’ve been, and perhaps the traces of other pieces before that as well. It’s interesting that very often when I’m working on pieces, I feel that I’m working very much outside my comfort zone and in a very different way, and yet when I hear the results, there’s lots of what I’ve done before in there as well. But I think in this case, the results are quite different, and I think that has a lot to do with, as you say, working with ELISION, and knowing what they’re capable of. So it wasn’t so much that I was thinking about stylistically what ELISION are used to playing, but rather just the potential I had for actually exploring a much more complex surface area, a much more finite gradation of rhythm as well. So you could have the same pitch material going on in several different instruments, but just very, very subtly displaced. So you almost get this sort of blurring effect, this kind of shimmering surface effect. Actually, when I first started writing the piece, I had the idea that it would go through a series of discrete forms, but that things might return, but in a slightly convoluted way. And in fact, the more I worked at the piece, the more I actually realized that what I wanted was just a surface, just a panel that would go on, well, could go on indefinitely. It would go on for ten and a half minutes but would have the sense of being much larger.

(1′ excerpt)

Yeah, it could have continued. With this group I have the sense that they’re happiest when they’re pushed to this total limit of endurance and concentration.

That’s right, that’s right. Yeah.

And you did that.

Yeah. And in fact, Daryl Buckley, the artistic director, had said, in a slightly joking way, “Give them something to do.” They’ve certainly got something to do in that piece.

Yeah, they have, there’s no question. And the other thing that really struck me being at the rehearsal yesterday was how hard the players were working to not be heard, to not stand out. And that seemed like this additional layer of difficulty. It’s like this perpetual motion, and a lot of activity, but you’re not supposed to hear any of it. It’s part of the larger texture.

That’s right. I mean, it’s all there. It’s a bit like looking at a tree in the middle of summer from a distance. Every leaf is there, and every leaf, and every small twig and branch is all part of what makes up that tree, but you can’t really take too much of that away before it looks like something else. But you don’t actually see the detail.

It’s not soloistic.

No. So I think it’s quite different in that respect to some of the other music that ELISION performs.

Yeah, that’s true. Last time I was at Huddersfield, you mentioned that you still didn’t know how to listen to the piece. I’m wondering if you’ve come to some ways of listening to it, and if your ideal would be to have one way, or a number of ways, or not to know.

Yeah. That’s an interesting question. I think initially, the difficulty I had was that the music’s moving so quickly that it’s very very difficult to get a tangible grasp on anything at all. So I seem to remember coming away from that first rehearsal just feeling a little bit empty, and wondering if the audience would have the same reaction—that you hear this flickering, fluttering surface, but it’s impossible to achieve a direct engagement with the music. And I certainly feel a lot more engaged now, when I listen to that music. But I still find it slightly perplexing, I have to say. I mean, I now know exactly where the repetitions occur within the music.

You can hear them?

Well, I hear them to some extent, but I still find it very difficult to find discernible points where the material repeats in exactly the same way. I should say, when I say exactly the same way it’s pages that repeat but with different articulations, which of course means that when that happens, different instruments come to the foreground. So one of my students actually, Pat Allison, said that for him it reminded him of skip reading through a book. So you’re taking some of the lines, some of the text, and words jump out at you, but you could quite easily come to the same page again, if that was possible in a novel, but not actually be aware that you’re reading the same page again. It’s quite a good analogy, I think, because the material is just so dense that it’s impossible, I think, to hear everything at once. So when we do cycle back to the same points, and the music’s on about 40-second loops, so every 40 seconds…

Only that?

Yeah, yeah. So we encounter the same points about 15 times within the work. But each time, certain instruments repeat, but others might change. But in certain instances, there are actual, literal repetitions of the page. So although the page is incredibly dense, 105 pages, actually a lot of the pages are photocopies or partial photocopies of other pages that are then amended and rearticulated.

How was it, working with the players and with the group? What was that experience?

It was wonderful. I mean they were incredibly encouraging, very very positive. It was a very affirming experience working with the group, and very enjoyable as well. I never thought I would write for ELISION, because I didn’t ever feel that where I was coming from aesthetically complied with the kind of thing that they did. But there was obviously some point of reference there. And yeah, they’ve been incredibly encouraging and supportive.

Did you try things out with them?

No, actually. I think circumstances prevented that a little bit, in that I just had to go away and get the piece together when they weren’t in residence at that time in Huddersfield. So just working with the knowledge of what they did, and to some extent taking some risks as well, I just sort of pulled the piece together.

I don’t think it would have happened without risks. I don’t think it would have worked.

No. But I think that’s something which I always try and do. I always try and work slightly beyond capabilities.

surface forms (repeating) is on ELISION’S transference CD.

Hi Jennie,

Yes for me, in working with Bryn, there was a small hint of the transgressive in performing a composer whose inclusion might surprise some, certainly those who are familiar with the work of ELISION from recent years. However, working with Bryn was not totally incommensurate with the artistic history and direction of the ensemble. In the early 90’s when ELISION had a strong vein of contemporary Italian aesthetic threaded throughout its concert work we had commissioned a major ensemble piece from Aldo Clementi. Aldo’s music, albeit in a different way to Bryn, is also unpretentious. Through engaging with various processes of repetition Clementi transforms the experience of listening to his music to one of perceiving an unchanging object-only the point of regard, if you like, alters. And in this way and also in respect to our Clementi CD of several years ago on Mode the work with Bryn seemed to extend our practice from these earlier artistic experiences. It was a great pleasure to work with Bryn during rehearsal and performance and I hope one day to revisit his piece.

Thanks for your thoughts, Daryl. I pursued this question with Bryn because it engaged me so much, for reasons that have a lot to do with the name of the blog and a real interest in musicians who are taking nothing for granted but stretching the boundaries, challenging thought, ear, technique… It could be termed working at the margins, but it actually has the effect of changing those margins. There are groups of musicians that cohere somewhat in the ways they are trying to do this, and a lot can happen and does happen through that shared interest and coherence, and the building of those relationships. I had imagined Bryn’s music in one of those areas, and ELISION’s work in another, and was very invested in both before I knew about this piece. The collaboration seemed quite genuine and mutually enriching, and all the more so, in my experience at least, for defying those expectations and finding a fresh form of coherence.

I’ll probably go back and edit this comment, but wanted to get this thought down at least in part.

Just from that little clip (and from my previous experience of Bryn’s work) the comparison with Clementi is really interesting and (I think) incredibly pertinent in a way that I hadn’t previously considered.

In the interview, Bryn’s comment that he came away from the rehearsal feeling ’empty’ reminded me a little of how I sometimes feel after listening to Clementi: there’s a sense of devastation and clearance (like deforestation), and it can leave me feeling quite bleak. But in case that sounds too negative, it’s an incredibly attractive kaleidoscope that after repeated listenings, you just hear more and more details. It’s like a fractal.

Thanks, John, for your thoughtful comments. They correspond to my own experience, too. All of the pieces on the transference CD, and so many I try to write about here, have the effect, I think, of raising fundamental questions about how to listen. It’s a subject that comes up powerfully in the video about ELISION’s 2003 performance of Barrett’s Dark Matter that recently surfaced. (More on that soon.)

I think your comments are absolutely fine and pertinent! Wouldn’t change them for anything!